An uncertain depth, as if something were lurking behind what we see…

An uncertain depth, as if something were lurking behind what we see…

Like a picture, or a personal vision.

The young woman peering curiously out the window-‐

The window is closed, there is no way through.

There the artist in the fallen contemporary world.

Grief, pensiveness, solitude,

Embittered, self-‐pitying and distrustful.

A believer who struggled with doubt.

A celebrator of beauty haunted by darkness.

The symmetries so essential in an icon-‐

Jagged, helter-‐skelter, fragments of horizontals and verticals juxtaposed.

Dramatic geometry and tantalizing fragments of what lies beyond:

The top of a ship’s mast, half a house, sections of shoreline

Silhouetted mountain top of firs and rocks

Barren trees and ruins rising against wintry skies

Rotting wood enclosing an overgrown and hollow mound

Cemetery gate posts tower unnaturally…

A thin and empty world of absences.

Of branches overlapped on branches overlapped on void.

Symbolic forms imbued with mysterious prescience,

And, once spotted they can again be lost-‐

So that they retain always their potential status as mirages.

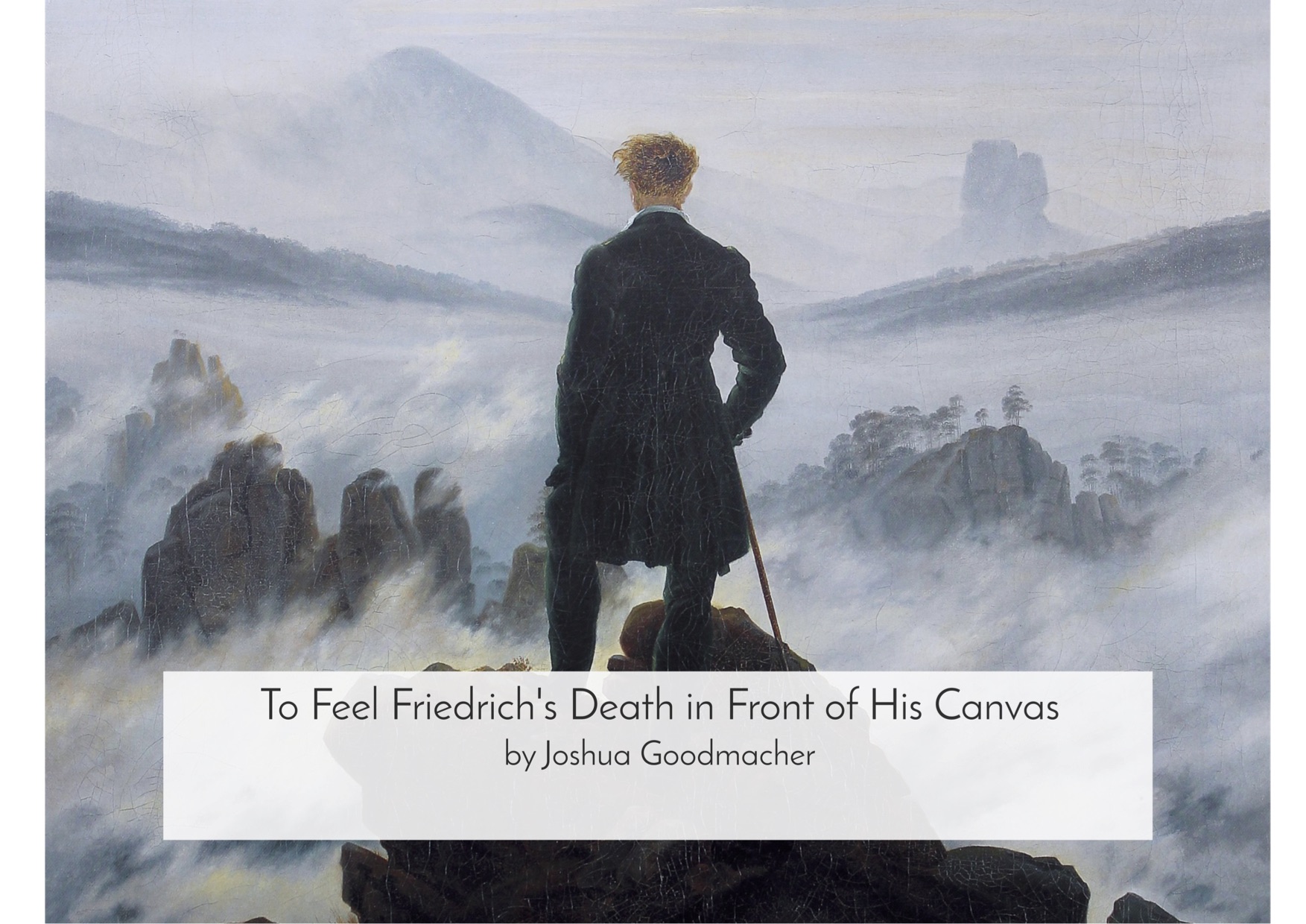

A landscape beheld by a halted traveler.

A traveler in this Eigentumlichkeit.

What is solid there has now become a fissure in space,

The image of saturation and overflow.

The visionary through painted light.

The turning away of God’s eye toward the hidden sun

Where religion would be merely a remembered promise-‐

Only the universal blank of pigments evenly applied,

Emptied of all human reference, all continuities of scale and space.

The infinite through the bathetic collapse of evocation.

To plunge suddenly…

A series of strokes

Elizabeth in 1782 and Maria in 1791 and Johann Christoffer in 1787

May 7, 1840

‘pulmonary failure’

This wall rears up like a barrier, blocking off the space that lies behind it, Which is discernible only as a sense of light offering a kind of promise…

Maybe this is one more personal reflection on death and the world to come…

An allegory on the transience of life and the promise of redemption beyond…

Or,

The anchor, sometimes just an anchor, rises before a wholly natural scene.

Is the deep notch carved in the white cliffs a rising accent or a falling one?

It is both.

An expiation:

This poem is built of stolen words. It is made of blocks of beautiful, intelligent fragments robbed, stripped, and manufactured into a new thing. A thing that is uncomfortably my own creation, and yet, not a single word can be called mine. A thing that is at once an artifact, an artistic piece in and of itself, and the embodiment of it’s own process of creation. It is perhaps best to explain it as such;

The process, an exploration:

This poem is a found word piece assembled from phrases copied out of Art History books and articles about the18th century painter Caspar David Friedrich and his paintings. The creative act consisted of me frantically reading these books, occasionally jumping randomly between sections, and transcribing down the fragments that struck me in the form of bullet points devoid of context. I then cut and pasted my favorite bits to fit the thematics, flow, and meaning of the poem I found myself wanting to create. Although, to be honest, the poem I found myself wanting to make changed with every phrase I copied. I edited as little as possible from each phrase, opting rather to let them stand on their own merits. But, why shamelessly abduct and adulter the words of esteemed Art Historians?

The most basic answer is that I love the language of Art History and Art Theory. It has a beautifully poetic, yet scholarly accent, a vocabulary and movement that, to me, begged to be resurrected in the guise of a poem. The charm of the language of Art History is especially apparent in the prose used to discuss the work of Caspar David Friedrich, who many view as a particularly poetic painter. His choice of color, his use of light, his subject matter are near impossible to put into language without sounding dactylic. In the end, I think it was both the subject, Caspar David Friedrich, and the scholarly lens of Art History that led me to this poem, and to this process.

From Friedrich’s own ideals I got the desire to investigate the notion of the creator and creativity through using a found poem technique. To find, for myself, where the impetus for a piece came from. He wrote, “a picture must not be invented, it must be felt.” and I wanted to explore that process. I wanted to create a work, about his paintings, from both an invented and felt source. It was for that reason that I gathered the phrases first, before any idea of the kind of poem or subject, besides a general notion that it should be connected to Caspar David Friedrich, and allowed the poem to develop from an already predetermined source. I wanted it at once to be an act of mimicry and creativity. A creative thing, a poem, built of the critique and an analysis of an entirely different creative thing, paintings and a life.

The poem itself, an object:

This poem, as its title perhaps too blatantly suggests, is about viewing the work of Caspar David Friedrich and thinking about his descent into obscurity and death, while simultaneously, it is about dealing with ones own mortality, and the way that fact influences the perception of his paintings. Friedrich as a painter was obsessed with personal perspective. His paintings were reflections of his own experiences of nature composed in a way that invoked both universal human perception and drew out the real experiences of individual viewers. He wanted to provoke the enormous feeling, the sublime feeling, that one experienced while sensing God’s presence through the natural world. Yet, by the end of his life he questioned his relationship with God and the project of his art itself. The poem plays with the notion of personal perspective as well, particularly in regard to the influence of education on the individual lens. It is about dealing with the depth of the

feelings that Friedrich’s work forces one to confront while, because of an education in Art History, experiencing his work through a biographical and critical lens. It is a poem about the conflict between experiencing an artists work emotionally and viewing it through a critical analytic lens, to finally answer the question, which is the correct way to view art? “it is both.”

Works Cited:

Vaughan, William, and Caspar David Friedrich. Friedrich. London: Phaidon, 2004. Print.

Koerner, Joseph Leo. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990. Print.

Hofmann, Werner, and Caspar David Friedrich. Caspar David Friedrich. New York:Thames & Hudson, 2000. Print.

Grave, Johannes. Caspar David Friedrich. Munich: Prestel, 2012. Print.

Prager, Brad. “Sublimity and Beauty: Caspar David Friedrich and Joseph Anton Koch.” Aesthetic

Vision and German Romanticism: Writing Images. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2007. N. pag.

Print.

Vaughan, William, and Caspar David Friedrich. “Ch. 6:Engagements with Naturalism & Ch. 7:

Observations on Art and Artists.” Friedrich. London: Phaidon,2004. N. pag. Print.