The actuality of a mass tragedy creates ethical obligations in light of its representation, and the argument stands that these incidents require a portrayal that is exhaustive, detailed, and in the case of the press, immediate. Depictions that do not adhere to these qualities hold ramifications of an undoubtedly public nature, as their audience comes away from the piece misinformed and thus unable to understand the plight of those who actually suffered. The majority of authors who publish works in response to tragedy

The actuality of a mass tragedy creates ethical obligations in light of its representation, and the argument stands that these incidents require a portrayal that is exhaustive, detailed, and in the case of the press, immediate. Depictions that do not adhere to these qualities hold ramifications of an undoubtedly public nature, as their audience comes away from the piece misinformed and thus unable to understand the plight of those who actually suffered. The majority of authors who publish works in response to tragedy

are doing so with decent intentions, especially if, as with Mo Hayder’s 2005 novel The Devil of Nanking, the incident in question has long been obscured

from the public’s eye. Nevertheless, the author’s original purpose does not compensate for a problematic implementation of content, which includes aspects such as writing style, visual imagery, subject and theme, and even genre. These components of literature, if dealt with incorrectly, can override the benefits of depicting a tragedy. Although the quote “avoid pandering to lurid curiosity” (Pumarlo) comes from the Society of Professional Journalists and is thus intended for members of the press reporting on trauma, the sentiment extends to all media renditions of this nature. This foundational concept has an intriguing relationship to Hayder’s text, as the ethical duties associated with portraying the 1937 Nanking Massacre initially seem to contradict the novel’s genre as a thriller. However, Hayder appears to be aware of this potential misstep, and a comparison between her work and much of the coverage regarding recent acts of violence indicates that news media is instead the entity typifying the crime novel’s sensationalism and enablement of voyeuristic human instincts. The style of many of these news articles plays to the shock value of violent death, which encourages the

reader’s fascination with both the perpetrator and the pain of others. In contrast, Hayder’s treatment of the subject in The Devil of Nanking advocates

against this lurid approach by adapting the detective novel convention of

type characters for the purposes of representing tragedy. This work thus acknowledges the gravity of its subject through the severe opposition of its central figures: while the perverse character of Jason embodies the morbid fetishism that can be perpetrated by the press, the heroine, Grey responds to the text’s tragic content in a way that addresses the position of the victim and the importance of vicarious grief in the audience’s response.

Pumarlo’s journalistic claim, “[tragedies] are the type of stories that should be reported as a living history of communities” resurfaces in the piece “Vicarious Grieving and the Media.” This article, which focuses on the emotional response to loss, shows the media’s potential to affect healing. Its guiding concept is that one’s expression of grief “provides a psychological release that enables the mourner to vent his or her pain” (Sullender, 192). When the voicing of this emotion is put in a social context, Sullender argues that humans will instinctively respond with empathy that creates a shared sense of anguish (192-‐193). Accordingly, this claim of cause and effect is the basis for vicarious grief, or “‘the experience of loss and consequent grief or mourning that occurs following the deaths of others not personally known by the mourner’” (193). The textual representation of loss provides a similar function in that it allows for bonding among victims, witnesses, and their larger audience, and the opportunity for this empathetic response is in fact heightened by the global expansion of news networks in the modern day. “[T]he media has increased our emotional attachment to places, people, and events in the larger world,” Sullender says, “thus setting the stage for a greater incidence of, and occasion for, vicarious grieving” (196). Nonetheless, more traditional functions of journalism are just as vital, and in conveying this argument he states that the move toward closure involves “a process of making meaning out of the tragedy” (196). The presence of the news media in relaying tragedy is crucial precisely because it can act as a “meaning maker,” an entity whose foundation in storytelling can be used to create respectful narratives of grief.

The end of Sullender’s article shifts its focus from the advantages of media coverage to the potential shortcomings in creating an “over-‐exposure” to tragic material. The author mentions that, due to scientific advances that have extended the average human life, many of us are personally exposed to less natural death. Meanwhile, the media’s focus on unnatural tragedies means that this institution is the one “teaching all of us, particularly our younger generations, how to grieve and mourn” (199). Although this modified societal relationship to mortality is not automatically harmful, the

angle of emphasizing the more newsworthy and shocking fact of violent death and limiting reportage of grief to “a short, intense phenomenon” may contribute to “a whole generation being raised on a dynamic of desensitization” (199). Consequently, the lack of healthy outlets through which to express sorrow can give rise to emotions that are less rooted in responding to a tragedy and instead stem from curiosity about death. This approach to representation can be interpreted as verging on the Society of Professional Journalists’ warning against “sensationalism” (Pumarlo). Taking advantage of morbid drives diverts attention away from those suffering physically and emotionally, in effect compromising tendencies toward empathy that are paramount in communally understanding the repercussions of human atrocity.

A striking example of this type of media distortion appears as a result of the 1999 Columbine High School killings, which left 23 students dead and more injured after the two perpetrators attacked with guns and bombs, finishing by taking their own lives. Due to its horrifying scope, coverage of the incident was both detailed and timely, qualities that could theoretically aid the victims by helping the nation to vicariously grieve. Various studies, however, show the distorted nature of the news stories surrounding the incident. While information on the killers’ actions and their lives prior to the murder was arguably necessary in relaying the facts (Pumarlo), “most [of the coverage on individuals] referred to [shooters] Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold” (Schildkraut & Muschert, 35) rather than their victims. These skewed depictions give way to audience speculation and the notion of the incident as a terrifying scandal whose causes remain unfathomable, thus showing the link between the emphasis on “‘offender-‐centered reporting’”

- and the claim of a “discourse and politics of fear” (1356) that David Altheide makes in his piece on the tragedy. In the essay, he describes how depictions of the violence at Columbine expanded into discussions of societal issues, such as “youth problems,” “discipline concerns at school” (1356), and the national concern of terrorism (1357). While their broader relevance should not go unnoticed, the value of discussing these issues is limited by the dramatized mode of their portrayal. According to Altheide, the narrative format of news partially draws on “information technology, commercialism, and entertainment values” (1355) in addition to fact-‐based reporting. The end result of this approach to representation is an atmosphere of public terror, casting the media as a “machine that trades on fostering a common definition of fear, danger, and dread” (1356).

The idea that tragedies can be distorted to exacerbate an audience’s panic is not dissimilar to the notion of their ‘entertainment’ potential. In this scenario, the author’s framing of events utilizes the reader’s understandable

emotions of fear and uncertainty, exploiting them for shock. In one report on Columbine, the Los Angeles Times constructs a lede that reads as if it were a

page from a hardboiled crime novel:

“Laughing as they killed, two youths clad in dark ski masks and long black coats fired handguns at will and blithely tossed pipe bombs into a crowd of their terrified classmates Tuesday inside a suburban high school southwest of Denver, littering halls with as many as 23 bodies and wounding at least 25 others. The gunmen, embittered youths reportedly fascinated with paramilitary culture, kept police sharpshooters at a distance for more than four hours before they apparently used their guns on themselves” (Cart, Slater & Braun).

In contrast to the factual, somber tone that one would expect, this opening plays to the audience’s imagination, utilizing images of heartless, crazed villains found within texts of this suspenseful genre. This article is in fact one of many to adopt that style of writing: TIME magazine, a respected publication known for thoughtful material, came forth with a cover story featuring the title “The Monsters Next Door: What Made Them Do It?” This cover returns to Schildkraut & Muschert’s concept of offender-‐centered reporting, as the largest and most vivid color images on the page are those of Klebold and Harris; in contrast, the magazine affords lesser importance to images of the victims, which are considerably smaller and shown in black and white. While the Society of Professional Journalists’ ethics endorse the duty to create a narrative for reprehensible actions, these representations attach unwarranted melodrama to the events that implies a disconnect from reality.

The mechanics of the crime novel work to create a sensation of excitement in the reader, which reveals further parallels between this genre of literature and the flashy, entertaining style found in coverage of tragedies. The constant in novels of this type is “the ‘whodunit’ question” (Pyrhönen, 24) that controls the arc of the plot; when applied to news media, this convention surfaces as the query of what motivated the offender. As the reader learns the cause of the issue at hand, he or she is provided with the feeling of relief from uncertainty. However, when this legitimate approach to coverage of tragedies is conflated with sensationalistic writing, the goal of providing an

audience with greater peace of mind and an opportunity to vicariously grieve becomes secondary to satisfying curiosity. In detective fiction this premise is often paired with the promotion of “national culture values” that ultimately triumph over the “‘alien’ adversary” (25), a stock character whose evil is horrific yet captivating. Columbine coverage such as TIME’s use of the word “monster” to describe the shooters arguably puts them in a similar role, painting the two as less than real. While crime novel plotlines with glamorized danger are in part designed to create that emotional rush of excitement, this framing is antithetical to reports on tragedies, which should be depicted so that the public can see the reality of the incident and empathize with those affected.

The claim that tragedy and vicarious thrill seeking belong to separate realms immediately calls into question the premise for The Devil of Nanking. Mo

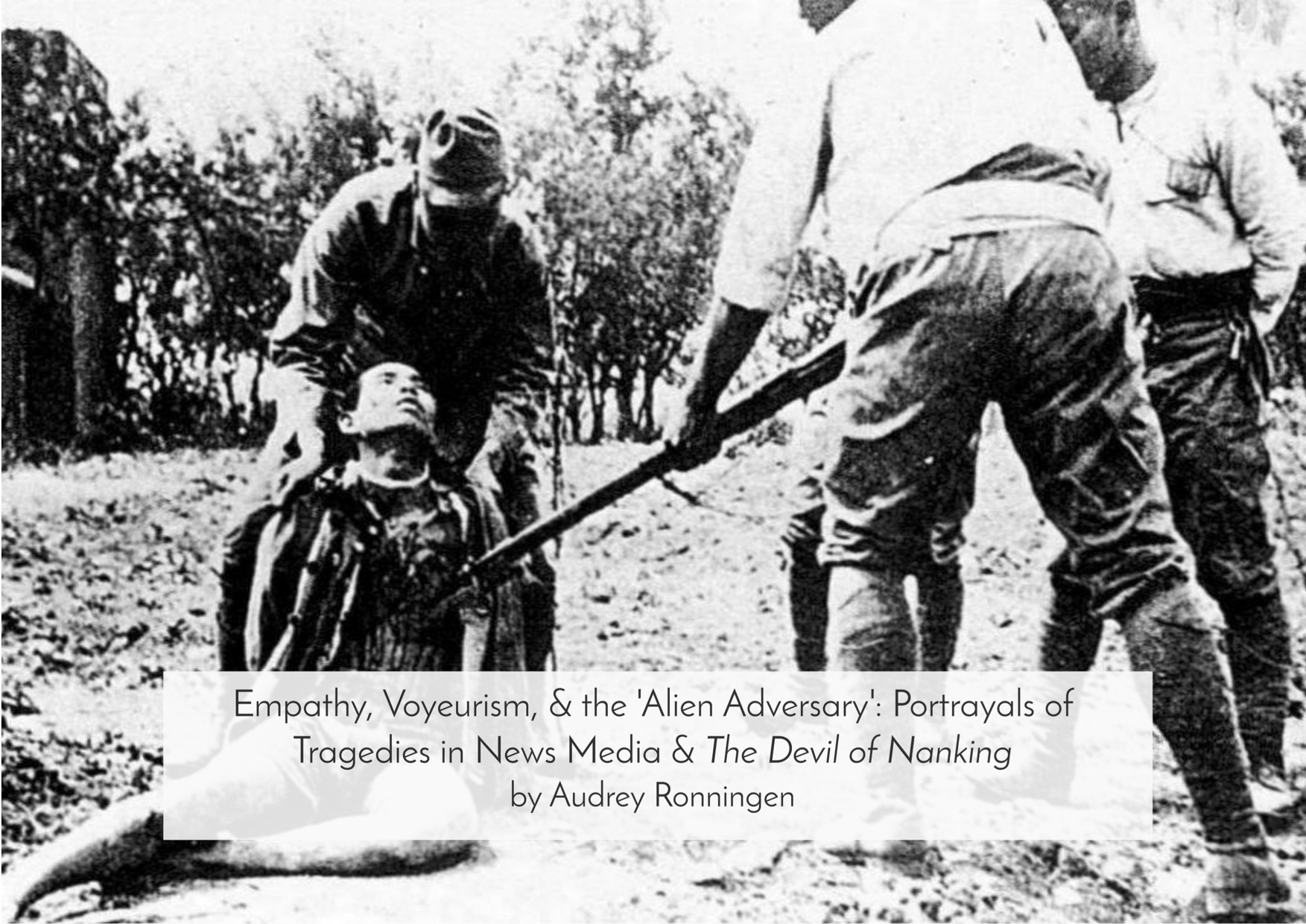

Hayder’s recent novel is one of her many ventures in crime fiction, in theory problematizing her choice to address the Nanking Massacre. Furthermore, Hayder is tasked with being among the first novelists to portray this atrocity, which has largely been kept quiet due to a combination of global unawareness and purposeful denial on the part of the Japanese government. The novel’s opening includes words of thanks to Iris Chang, whose extensive

work on the massacre emerged as the first major undertaking of its kind. In The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II, Chang details

how Japan’s initial 1935 occupation of China led to the takeover of the titular city and a final death toll numbering between 250,000 and 350,000 Chinese soldiers and civilians (Whitten). The review of Chang’s book highlights her point that these killings were not only widespread but especially senseless and malicious in nature: “For the women, rape usually preceded their murder. Indeed, from Japanese Army reports and letters sent home by participants, the killing of captured Chinese soldiers became something of a sport with awards going to the Japanese captors who killed the most men in the shortest time” (Whitten). Given the severity of this incident, it seems that the style of Hayder’s text would create a glorification of evil almost identical in nature to some of the Columbine coverage. However, Hayder’s cautioning against voyeuristic urges seems to be a stronger undercurrent, which is achieved in the characterization of the protagonist, a British woman who refers to herself as Grey, and her foil, an American named Jason.

The latter character holds an unusual presence in that he is primarily defined not by his own interests, but by his manner of relating to others. Finding herself with neither means nor shelter upon arrival in Tokyo, Grey spends

the night sleeping in one of the city’s parks and wakes to a young man who has been watching her (Hayder, 29). This action signals Jason’s interest in the narrator, yet his declaration “‘you really are weird’” suggests that Grey is intriguing solely because of the unorthodox setting in which she appears and her odd clothing (30). Subsequently, his abrupt offer to rent her a room seems predicated on his belief that “‘You’d be funny in our house’” (31), as the implied allure of the “‘weirdo’” (31) is a motif that develops in increasingly disturbing ways throughout the text. After Grey has accepted his

offer, she learns that other tenants refer to him as “a strange one” who watches graphic videos with titles in the vein of Faces of Death and claims of Genuine autopsy footage! (78) Later, when Grey enters his room, she is met

with photos of “young Filipino men nailed to crucifixes [and] vultures gathering for human flesh on the incredible Towers of Silence at a Parsi funeral” (79). The structure of one’s personal space is often an indirect way to articulate elements of identity, and these images build on the idea that Jason’s passions lie in observing others thrust into extraordinary or tragic situations.

While the tactic of associating Jason mainly with voyeurism can be seen as a novelistic flaw, constructing him with an absence of true subjectivity instead allows Hayder to analyze a single aspect of human nature with regards to her text’s larger themes. The character’s emphasis on processing outside information shows broad similarities to the media spectator; furthermore, his personal compulsion toward images of others’ pain specifically parallels the lurid curiosity that types of news coverage can provoke in readers. This aspect of Hayder’s approach to characterization becomes evident in Jason’s interactions with Ogawa, the female bodyguard to the yakuza leader who frequents the nightclub where he works alongside Grey. Although Grey is puzzled by Ogawa’s “wide, masculine shoulders, long arms, sinewy legs crammed into large, highly polished black stilettos” (70), Jason takes a marked interest in this ‘difference,’ and even after he begins a relationship with Grey he lingers on this other character’s physicality. “‘She? Is it a she? I can’t help wondering,” he says. “I’d like to find out. I’d like to know what she looks like naked. Yeah, I think that’s mostly it’” (208). Although there is the implication of sex, Ogawa holds this appeal for Jason precisely because he assumes her body to be ‘malformed,’ with the looming question of whether she is even female.

Viewing Jason as a stock representation of the intermingling between interest and horror, one can see how this character addresses some of the

thriller conventions listed in Pyrhönen’s work. Jason’s desire to find “something mangled” (Hayder, 215) takes on added significance when the text reveals Ogawa’s connection to Nanking both as a murderer with methods of equivalent brutality (141) and as an employee of the elderly mob leader Fuyuki, who took part in the killings as a young soldier (348). The mystery and intrigue of the plot involving Ogawa and Fuyuki is more typical of detective fiction, making it in theory an ethically inadequate means of representing the Nanking Massacre. However, Jason’s presence in this scene instead helps assert that Hayder is both aware of her choices and active in shaping a certain reader mentality. Jason holds a detached view of Ogawa as the “’alien’ adversary” (Pyrhönen, 25) -‐ an unnatural menace whose actions are cause for fetishism rather than vicarious grief -‐ and his viewpoint is arguably comparable to the mindset of readers who fell prey to glamorized depictions of Klebold and Harris. Nevertheless, Hayder is able to prevent the reader from also perceiving Ogawa and Fuyuki in this manner by drawing on Jason’s value as a stock character. While his innate response to unsettling material represents one possibility within the range of human emotions, his analogous lack of empathy acts as a mechanism to warn the audience, ensuring that they recognize their own full agency. This technique of portraying Jason as a base, unfeeling villain is admittedly didactic but also necessary in this case, as it allows the reader to consider the effects of Ogawa and Fuyuki’s crimes rather than viewing them as mere ‘aliens’ or ‘monsters’.

The novel furthers its stance on the representation and consequent audience reception of tragedy by examining the motives of Grey. Throughout this plotline Hayder constructs a metanarrative that becomes apparent only when considering questions of genre and ethics in literature. Hayder establishes her protagonist’s self-‐described obsession with the Nanking Massacre (19), and the tenuous circumstances of Grey’s fascination mimic the broader notion of whether a crime novel can represent such a topic without stirring sensationalistic appeal. As Grey seeks out Shi Chongming, a Chinese professor who specializes in the incident and is purported to have the historical account she has been searching for, she shows him examples of her work on the massacre. While her research is impressive in its precision, it is in fact this extreme attention to detail that Shi sees as eerie and even disturbing, given the gruesome subject matter. After Grey shows him an intricate sketch of “‘exactly three thousand corpses’” modeled after “‘the city at the end of the invasion,’” he warns her that the topic has been deeply repressed in Japan and then admonishes, “‘[t]his is my past you’re talking about’” (15). These last words show that he regards her preoccupation with

Nanking as uncaring, and the possibility that Grey’s interest is nothing more than voyeurism recurs in Jason’s claims that the two of them are alike in their fascination with morbidity (182). This question also marks a return to the metanarrative, and considering the novel’s events as a whole, Grey’s early interaction with Shi brings to light one example of the flaws that could stem from depicting the tragedy in thriller format. However, the text later comes to distinguish between Jason and Grey, using the downfall of their relationship as evidence of their difference in character.

As Jason and Grey grow closer, his impatience with her indicates that he merely wants to discover what she is hiding about her past (187). Although Grey is at first drawn to Jason’s charm and later becomes intimate with him, she is initially unable to show him the disfiguring scars on her stomach. However, when she decides to trust him with this personal trauma that has motivated her research on Nanking – her decision to stab herself while thirteen years old and pregnant, in order to ‘give birth’ alone – she does so as an act of confidence, with the hope that he will understand. Instead, he is captivated by the sight: “He got up and took a step towards me, his hands lifting up, reaching curiously to my stomach, as if the scars were emanating a glow” (211). He proceeds to examine Grey’s stomach, asking shockingly specific questions such as “‘Did [the knife] go deep here? …That’s what it feels like’” (214). Grey realizes, “there was something horrible in his voice…as if he was taking immense pleasure in this” (214), and she thinks, “I imagined his face, smirking, confident, finding sex in this, sex in the scars I’d been hiding for so long” (215). Jason’s cold response confirms his fascination with the trope of the “freak,” a quality that opposes the sensitivity required in portraying tragedy. The significance of this interaction is further clarified when theoretically transposed to the context of a news story. The sensitive, traumatic nature of Grey’s past places her in the position of the victim, who would be aided by this opportunity for narrative that would ideally lead to a community of support. In contrast, Jason is again perceived as the reader who appropriates this content, regarding graphic scenes with stunned awe rather than listening to the victim’s account, and thus failing to grieve vicariously. This scene also utilizes the flat portrayal of Jason to enhance the metafictional aspects of the text. There is no sense of empathy or remorse in his reaction, both of which would lend nuance to this character, and his villainy prevents the reader from forming a similar interest in the grim story behind Grey’s scars. Instead, the text works with the assumption that the audience will identify positively with its heroine, Grey, thus placing the reader into the role of the empathetic reader.

The sympathetic portrayal of Grey’s backstory is tied into the larger context of Nanking, and the novel concludes by using this protagonist to embody another facet of responding to tragedy. Both the reason behind Grey’s self-‐ mutilating act and her subsequent interest in the massacre are initially ambiguous, and although she claims that her child’s death was not intentional (216), the audience is likely to not be convinced on either account. However, this withholding of information also works to a different end. An atmosphere of mystery is a central component of the crime novel, specifically with regards to the main character’s past and present motives;

consequently, one can see that Hayder’s emphasis on ethicality thus far does not prevent The Devil of Nanking from engaging with elements that make it

an authentic thriller. As the ending returns to the ethics of representation, though, the symbolic role of Grey’s character shifts from that of victim to that of the media consumer. At the end of the novel Shi plays the film footage that Grey has been searching for, as she believes it to show evidence of a particularly horrific practice that she once read about. She sees the image of a Japanese soldier ‘extracting’ a pregnant woman’s child through her stomach (352); however, we are surprised to learn that “[the infant’s] hands were moving. Her mouth opened a few times…she was alive” (353). This brutal procedure is done in the same manner as Grey’s attempt to ‘give birth’ as a teenager, suggesting that the death of her daughter was truly accidental, and that against all logic, she used this incident as confirmation that her own child would also survive. Additionally, Grey’s act can be interpreted as a response of mimicry that implies her emotional identification with the women of Nanking. It is possible that she chose to deal with giving birth in such an unusual and disturbing fashion because it would allow her to understand the massacre victims’ pain in a severe, literal way. Although Grey now recognizes the error in her decision, it is still crucial to interpret its meaning in strictly figurative terms that are reflective of the character’s unstable, desperate circumstances (215), not as a promotion of self-‐harm when dealing with strong emotions. Nonetheless, Grey’s wish to put herself in the position of the victim shows that she is attuned to the realities of Nanking, marking a clear instance of vicarious grieving. The thematic implication of this type of response recalls the proper role of the media consumer, suggesting that the empathy of Grey’s act –not the act itself – serves as a template for processing tragic material.

Although the ‘alien adversary’ is drawn from texts of Hayder’s genre, its correspondence to real life has created settings in which many of these

offenders are seen as “freaks” whose violent actions border on harmless fantasy. This detachment from reality in textual representations prevents the reader from forming the type of empathetic response that has proven most

effective in helping victims cope. The ‘alien’ figure of evil in fact appears in The Devil of Nanking, yet Hayder is careful to ensure that it does so in altered

circumstances. While the first example, Ogawa, could be interpreted as attributing to sensationalism, Hayder uses Jason’s obsession with her to connote his shameful role as a perverse voyeur. As a result, readers are urged

to disassociate themselves from this character by not indulging their own morbid curiosities in response to the text. The Devil of Nanking hints that this

trope of voyeurism extends to Grey, as much of the novel’s mystery stems from the question of whether her concealed past and her present obsession with Nanking are indicative of evil. However, the end of Hayder’s text shows this character’s shocking yet symbolically valid roots in empathy, indicating that vicarious grief is one of the only appropriate goals in portraying a historical atrocity of this magnitude.

Works Cited

Altheide, David L. “The Columbine Shootings And The Discourse Of Fear.”American Behavioral Scientist 52.10 (2009): 1354-‐1370. Academic Search Complete. Web.

Cart, Julie, Eric Slater, andStephen Braun. “Armed Youths Kill Up to 23 in 4-‐Hour Siege at High School.” Los Angeles Times 21 Apr. 1999: n. pag.Los Angeles Times.

Web. <http://articles.latimes.com/1999/apr/21/news/mn-‐29502> Hayder, Mo. The Devil of Nanking. New York: Grove, 2005. Print.

Pumarlo, Jim. “SPJ Ethics Committee Position Papers: Reporting on Grief, Tragedy and Victims.” Society of Professional Journalists. N.p., n.d. Web.

<http://www.spj.org/ethics-‐papers-‐grief.asp>

Pyrhönen, Heta. “Five-‐Finger Exercises: Mika Waltari’s Detective Stories.” Orbis

Litterarum 59.1 (2004): 23-‐38. Academic Search Complete. Web.

Schildkraut, Jaclyn, and Glenn Muschert. “Media Salience and the Framing of Mass Murder in Schools.” Homicide Studies 18.1 (2014): 23-‐43.SAGE Publications. Web. Sullender, R. “Vicarious Grieving And The Media.”Pastoral Psychology 59.2 (2010): 191-‐200. Academic Search Complete. Web.

Whitten, Robert C. “The Rape Of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust Of World War II

(Book).” Journal Of Political & Military Sociology 29.1 (2001): 192. Academic Search Complete. Web.

An uncertain depth, as if something were lurking behind what we see…

An uncertain depth, as if something were lurking behind what we see…

The actuality of a mass tragedy creates ethical obligations in light of its representation, and the argument stands that these incidents require a portrayal that is exhaustive, detailed, and in the case of the press, immediate. Depictions that do not adhere to these qualities hold ramifications of an undoubtedly public nature, as their audience comes away from the piece misinformed and thus unable to understand the plight of those who actually suffered. The majority of authors who publish works in response to tragedy

The actuality of a mass tragedy creates ethical obligations in light of its representation, and the argument stands that these incidents require a portrayal that is exhaustive, detailed, and in the case of the press, immediate. Depictions that do not adhere to these qualities hold ramifications of an undoubtedly public nature, as their audience comes away from the piece misinformed and thus unable to understand the plight of those who actually suffered. The majority of authors who publish works in response to tragedy