Difficult topics in literature–rape, torture, and genocide–are often surrounded by ethical criticisms. The ethics of representing traumas in literature is a field replete with opposing views, and many authors have reservations about writing acts of trauma because of the effect it can have

Difficult topics in literature–rape, torture, and genocide–are often surrounded by ethical criticisms. The ethics of representing traumas in literature is a field replete with opposing views, and many authors have reservations about writing acts of trauma because of the effect it can have

on those who have been traumatized. As literary critic Cathy Caruth writes about this ethical dilemma: “the unremitting problem of how not to betray

the past” (Caruth’s italics, 27). In this essay I will discuss the various methods of representing trauma so as not to fall into the cliché–as Coetzee puts it–of “spy fiction” (Coetzee, “Chamber” 362). Iwillalsoaddressthe crucialroleofthereader,astheauthor’stargetaudience should dictate the depth of the trauma being described. Lastly I will prove that no matter the

trauma, literature must represent these times when humanity is at its lowest. Although novels like Disgrace may be difficult to read for victims of

rape, it is imperative to acknowledge its message is meant specifically for the person who does not understand it. This tactic to which critics refer as “Crossing the line” is necessary and integral to the ethics of representation, as the author’s goal should be to use the sensitive subject in a way that discomforts the reader. Giventhisstandard, I will study various authors’ methods of how they cross the line in a way that nevertheless ethically represents their trauma to the target audience. There are four parts to this thesis, which will outline and define ethical representation

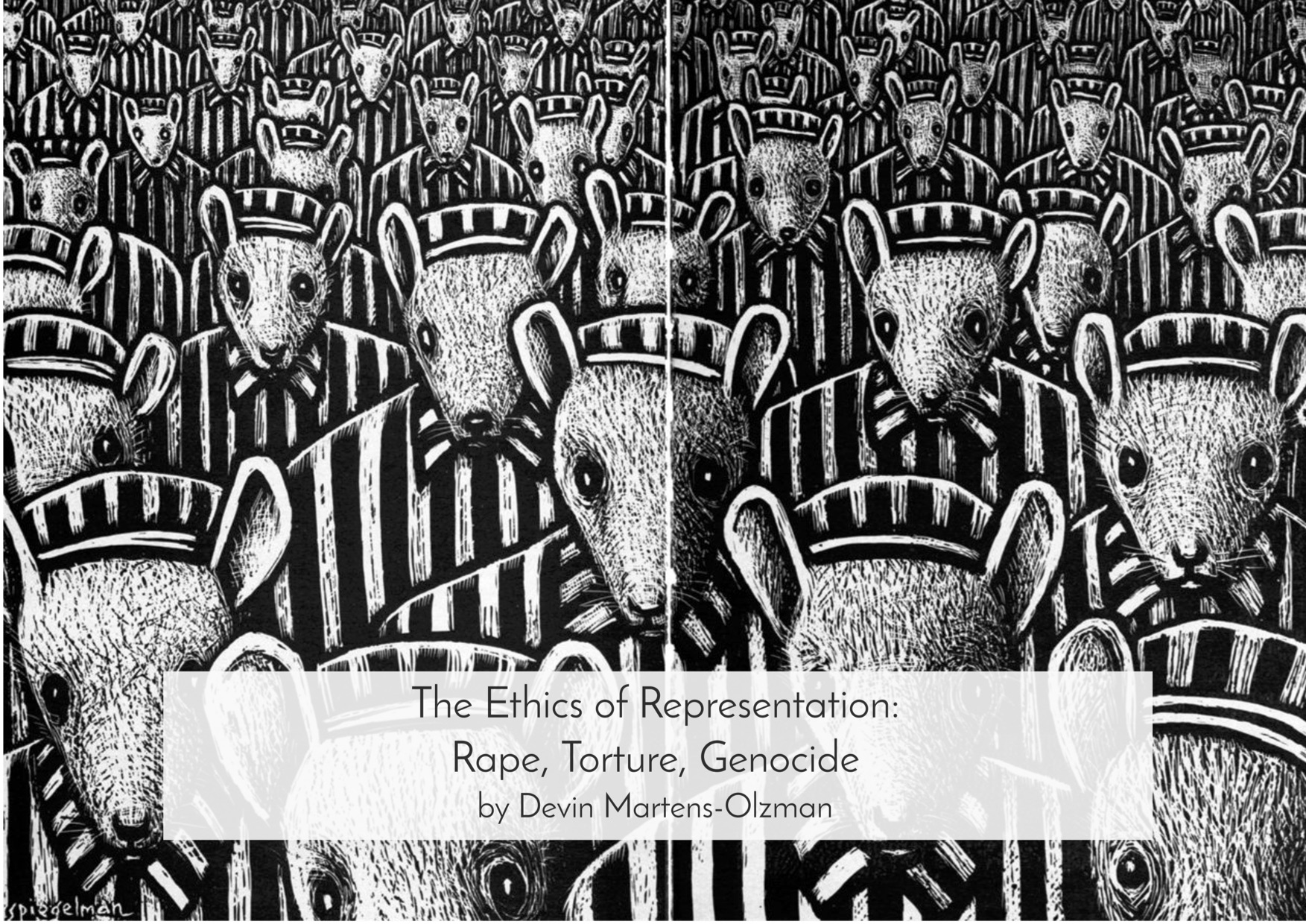

through close readings of J.M. Coetzee’s novels Waiting for the Barbarians and Disgrace, ErnestHemingway’sshortstory “Hills Like White Elephants,”

Art Spiegelman’s graphic novelMaus, and theImmortalTechnique song “Dance with the Devil.

Ethical Considerations: Placing the Reader in the Position of Being “Traumatized”

Texts concerning the ethics of representing traumas like rape, genocide, or torture are often in danger of falling into a suicide gorge, positioned above a symbolic tightrope between immense cliffs. On one side lies the readers of the texts: those who will critique it, laugh and cry while reading it, and deem the literary worth and popularity of the text. On the other side lies the victims– past, present, and future–who have experienced the trauma portrayed in the text. Walking on the tightrope is the author, balancing his or her own representation of the trauma and trying to represent something that has often been labeled as “unspeakable.”

It is important for both the author and the readers to realize that the text should not be meant for the victims of the trauma. Maus was not written for Holocaust survivors, just as Waiting for the Barbarians

was not written for tortured individuals. Texts like this are meant to illustrate–and to a certain extend traumatize–the intended audience with little experience of the incident itself. Although some may argue that it is unethical to place the innocent reader into the shoes of the traumatized victim, I argue this is the essence of the genre. Trauma literature should impact the reader, give them a representation– however minuscule in comparison –of what it was like to be raped, to live through the Holocaust, or to merely witness a fellow life being tortured.

There are some critics who find the representation of genocide and other traumas deplorable. The often-‐cited critic of Holocaust representation, Theodore Adorno states, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” (34). Adorno’s premise is summed up well in a later book, in which he writes, “When even genocide becomes cultural property in committed literature, it becomes easier complying with the culture that gave rise to the murder” (35). Granted, by depicting topics as difficult as the Holocaust the author also allows the representation of Nazi totalitarianism to continue. However,

even if it were possible to show one without the other it would be an inaccurate version of the past, as the aim of representation is accuracy and depicting Nazis is thus a necessary evil in representing history. Adorno warns against reification within such a complex topic like the Holocaust, yet this does not signify it is hopeless to attempt. On the contrary, it is imperative to represent these topics, particularly in literature and media. The human experience is unique in that we commit atrocities against each other unlike any other animal species on Earth. Speaking of the Holocaust does mean speaking of Nazism, and humanity must remember this stain on human history to prevent similar atrocities from happening in the future. This is something that has been happening since civilization began and covering it up, misrepresenting it, only further perpetuates the arrogance that humanity is above committing these traumas. The purpose of texts is to illuminate readers about the human experience, and as trauma is no different, its representation must also catalogue all perspectives, not just the victim’s.

An obstacle many authors face when writing about trauma is offending victims. This could be due to how the victims remember their own trauma, or simply because it is a memory they do not wish to go through again. Even those who know victims of trauma may feel representations are insensitive to those who have been through them. Spiegelman struggles visibly with this, when Vladek tells Art, “No one wants to hear such stories” (Maus I 12). Vladek knows that his story is not one people read for comfort or pleasure, and it is apparent that Vladek literally runs out of energy remembering

his past. After

describing a

mass

transportation

of around 100,000 Jews (including himself and his wife Anja) to Auschwitz, he looks sad and dejected:

(Maus I, 151).

Here we see Vladek, head in hand, visibly exhausted from retelling his past. His physical exercise on the stationary bike parallels the emotional toll of the victim reliving his own trauma through the act of retelling. Similarly, Vladek becomes upset and distant from his son upon reading his comic “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” because it forces him to recall his wife’s suicide. Thisisworsenedbyhavingto read it through the lens of his son and relive his trauma through another’s eyes. The act of re-‐experiencing trauma is difficult, and consequentially requires meticulous examination within the ethics of representation. Inthecreationofthisbook, Vladek and Artie consequently make a sacrifice together to relive their trauma and represent it to the world.

There are several methods of ethical representation considering traumatic experiences. First person narratives such as Maus are ideal because they do not attempt to give a full description of an over-‐arching traumatic event like the Holocaust. This narrowfocus allows the intended audience to put themselves into the mind of a single character, so they do not simply learn about the trauma, but experience it. However, ultimately it is difficult for the victim’s desire to relieve himself of traumatic memories to coexist with accurately educating the reader of the trauma. Maus addresses this issue as well, when Artie asks his father if he saved any of the letters of correspondence between himself and holocaust victims:

(Maus II 98).

Here we see the Holocaust survivor attempting to distance himself from trauma through destroying evidence that it even occurred. The dichotomy

between the Holocaust survivor seeking to destroy evidence of his trauma and the need to represent the trauma is shown throughout Maus. When Vladek tells Artie he burned Anja’s diaries of the war, Artie calls him a “murderer” (Maus I 159), representing Vladek as an ironic survivor who himself is guilty of murder. This is what makes representation so difficult: those affected by trauma are often the ones who choose not to speak about it. In this way it is imperative to know that trauma representation is not aimed at those who’ve been affected by the trauma, but everyone else. It is up to one brave victim to sacrifice his own sensibility and relive the traumatic moment in order to speak to the rest of the world.

J.M. Coetzee touches on this same paradigm of representation in Waiting for the Barbarians. In this genre characters often question the ethics of placing

innocent people in traumatic experiences, which parallels the text’s own objective of traumatizing the reader. Although all trauma literature seeks to traumatize or educate the reader about trauma, it should also bring to light the ethical dilemma of doing so. The Magistrate is made to write up a report on the torture and death of a prisoner, and Colonel Joll tells him, “‘…the prisoner became enraged and attacked the investigating officer. A scuffle ensued during which the prisoner fell heavily against the wall. Efforts to revive him were unsuccessful’” (6). When the Magistrate questions the guard with Joll to corroborate his report, he admits he was told what to say to the Magistrate and also confuses the facts on the incident (7). Still, the Magistrate’s own attempt at writing down Joll’s crimes in the form of a letter to the capital prove unsuccessful, which shows the difficulty of trauma representation (66). The inability of the Magistrate to write about torture alludes to the trouble many authors face when attempting to represent traumas like torture. Representing torture is rarely done accurately by objective texts like police reports and history books, so it falls to literature and creative texts to tell this story. Often those reading trauma literature are searching for answers about humanity and how we can commit these terrible acts against each other. The Magistrate’s healing of the tortured barbarian girl is his method of both distancing himself from Joll as well as attempting to understand torture: in a sense he “reads” the girl, trying to imagine himself in her position. However, his experience brings only confusion, guilt, and anger to the Magistrate. He does not find that his healing helps his own guilt, as he admits he “must assert [his] distance from Colonel Joll” (50). The Magistrate’s ultimate decision to take the girl to her people was an act of kindness, but it also stemmed from his need to take a stand against Joll the Empire, and possibly a subconscious

desire to be tortured himself and thus understand torture.

It is only once the Magistrate is tortured that he truly understands the experience. He says of his “fellow-‐creatures”: they have “no recourse but to turn their backs to the wind and endure” (177). This alludes to the role empathy plays in ethical representation of trauma. While there is no way to wholly represent trauma, even placing someone in the role of the victim is important, and it creates a link between the reader and the victim through empathetic response and understanding, instead of guilt and anger. As the reader only sees the story through the lens of the Magistrate, his trauma is ours, and through that we understand a little of what he went through. Trauma representation seeks to place the intended audience into a position to empathize and understand difficult topics, and the Magistrate’s own struggle to understand trauma echoes humanity’s trouble solving the same problem.

Disgrace,alsobyCoetzee, reveals the ethics of traumatizing the reader through David Lurie’s attempt at understanding Lucy’s rape. Lucy Lurie owns a small patch of farmland east of Cape Town in South Africa, and shortly after the end of Apartheid, her father David comes to live with her. When Coetzee describes how three men rob their house and rape Lucy, he never fully places the reader into the position of the victim. Similarly, only once does Lucy attempt to describe the rape to David: “ ‘It was so personal…the rest was…expected.’ (157).

Lurie’s position as the bystander to the rape can be related to the reader, since neither one can help the trauma victim through any other method besides empathy and understanding. Coetzee emphasizes the impotence of the bystander when he has David unsuccessfully and repeatedly ask Lucy to move away from her native South Africa, as well as asking Lucy to get an abortion (197). David begins to understand the process of empathizing with trauma when he asks himself if he “has it in him to be the woman” (160). He admits that to empathize he must try to imagine what it was like for Lucy, which outlines the problem that crossing gender lines poses as men try to understand trauma. Putting the reader in David’s shoes leads to this conclusion for us as well, even though David is unable to actually place himself in this position. His desire to stay near Lucy and help her through this time, on her terms, does show that he is willing to empathize with her situation and her desire to stay on the farm, even though he does not fully understand it. The notion that we may not comprehend trauma, like David’s

inability to understand Lucy’s, does not mean that as authors and readers we should ignore the problem of its representation. Instead it is best to try to empathize, even if anger and vengeance are easier to represent and feel.

Although Disgrace tackles questions of ethical representation, Coetzee complicates simple readings of trauma by setting the novel in post-‐ Apartheid South Africa. The easiest thing for Lucy to do would be to leave, to give up the farm and live in a new place, away from the men who raped her, like her father suggests throughout the novel. David notes to himself, “Lucy’s future, his future, the future of the land as a whole–it is all a matter of indifference,” but as much as South Africa is the home of the rapists, it is

also her home, and the new South Africa combines both the native African and the European descendantsofsettlers (Coetzee, Disgrace 107). David,

however is a member of the old South Africa, and he reflects, “In the old days one could have had it out with Petrus,” lamenting the power he has lost in his country (116). Lucy’s decision to stay at home reflects her desire to

become a part of the new South Africa, no matter the cost. She even asks, “what if that is the price one has to pay for staying on?” (158). Although her

question is in part due to Stockholm syndrome, she is also conflating her trauma with her role in creating a new South Africa. Lucy is not purely a martyr for her country, however, as her decision to stay stems from the pragmatic need for her to keep on living at her home. Lucy certainly does try to define the act as “justified rape,” only that the issue of post-‐Apartheid South Africa is one with multitudinous positions, and ultimately the question of forgiveness and empathy is crucial to the success of the nation. In this regard Lucy acts as a hero, sacrificing her own happiness for her country, just like Vladek must sacrifice his own happiness to retell his story in Maus. However, this is complicated by her pragmatism, as she must accommodate her neighbors simply to survive. The duality of Lucy as both a martyr and a pragmatic survivor is an important notion in accurately describing her position as a white woman in post-‐Apartheid South Africa.

The act of traumatizing the intended audience has become more common among underground hip-‐hop artists who target urban criminals or potentially criminal youths. It is worth noting that although the realm of hip-‐ hop is not characteristically thought of as a genre fit for literary criticism, I argue that in today’s media-‐saturated culture and the internet’s help in self-‐ publishing, the concept of what is literary is changing. Often it is the non-‐ canonical texts that reach the most people and have the capacity to change the way the populace thinks. This is particularly true with music, because

often it reaches different audiences than novels do. The representation of trauma can often be a “preach to the choir” genre, where those who already feel that the trauma needs to be stopped are those praising the text for its

work. Few conservative misogynists will pick up Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble just as few criminals will read The Nicomachean Ethics, by Aristotle.

However, a text like “Dance with the Devil,” must reach its audience forcefully and violently; to do anything else would risk falling on deaf ears. Its intense, vulgar imagery, though difficult to listen to, is done so to show rapists the horror of their own crimes. Coronel raps, “Billy was made to go first but they all took a turn / Ripping her up, and choking her…” (Coronel). Coronel’s gruesome descriptions are not just meant to disgust the listener for “shock value:” he raps “rape” graphically and revoltingly specifically because it is revolting. At his height of vulgarity Coronel raps, “he was looking into the eyes of his own mother…she cried more violently than when they were raping her” (Coronel). Ultimately the song reflects his audience, asking them the most difficult question: “What if she were your own mother?” Coronel’s message and underground rap genre cater to a mostly Black and Latino urban youth in the United States, some of whom live in the culture Coronel warns against and are more likely to be brought up by a single mother than other Americans. From 2000-‐2012 a staggering 67% of African-‐American children and 42% of Latino children were raised by single parents, compared with 25% of white Americans (Population Reference Bureau). Even the most hardened criminal has a mother, and most would wish her safety. Coronel’s representation of rape may be horrendous, but it remains a necessary evil, as the song targets the perpetrators of this crime and pleads with them to take a different path. The depth of abhorrence in trauma representation is dependent on the audience of the author. Coronel also places his listener into a role in which empathy is created, but his audience is the niche market of the criminal or rapist. That is why his lyrics are horrendous: he is speaking to a subculture of criminal that supports notions of drug dealing and gang violence.

The aim of trauma literature is to depict a traumatic event objectively while also traumatizing the reader so as to instill feelings of empathy and compassion for the victim. This requires a sacrifice be made for the victim, who often attempts to reconcile the damaging experience by forgetting it. Vladek burns letters and diaries to try to live after the Holocaust, lamenting, “All such things of the war, I tried to put out from my mind once for all…until you rebuild me all this from your questions” (Ellipses by Spiegelman, Maus II 98). It is a common coping mechanism of victims of

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (which Holocaust survivors undoubtedly have) to put their trauma out of their minds (“Post Traumatic Stress Disorder”). In The Magistrate’s case, he is unable to understand torture until he experiences it himself. True empathy comes from feeling the pain of others, which he learns throughout his experience with Colonel Joll. Ultimately it is not only ethical to traumatize the reader in ethical representation, but it is necessary to understand trauma. Representation cannot ever fully represent trauma, but creating empathy and compassion through literature and music is necessary for remembering the past beyond death tolls and history books. In the next section I will discuss several authors’ methods of representation of trauma from different angles, including the act of trauma itself, the importance of the witness, on the impossibility of telling, and the role of the torturer.

The Aftermath: the Psyche of the Witness

When trauma enters literary discourse, often the victim is interpreted, analyzed, and decoded ad nauseam. However, there exists another party that is similarly affected by trauma: the witness. Often the witness of a trauma feels guilt or shame in witnessing, or perhaps that they did not do enough to help the victim. Trauma literature almost always contains witnesses who are traumatized themselves by an experience with the victim or the perpetrator of a trauma, and authors who deal with ethical representation must accurately represent those who witness, because often simply the act of witnessing a trauma is traumatic itself.

In J.M. Coetzee’s essay “Into the Dark Chamber,” he refers to his novel Waiting for the Barbarians as “the impact of the torture chamber on the life

of a man of conscience” (362). The novel begins with the arrival of Colonel Joll, a military emissary from the Capitol, and his torture slowly converts the Magistrate against the very empire he swore to protect and serve. Initially the Magistrate goes hunting with the Colonel and maintains a peaceful relationship with him, but throughout the novel the Magistrate begins to distance himself from both the Empire and Joll. When tending to a tortured child’s wounds, he says, “It has not escaped me that an interrogator can

wear two masks, speak with two voices, one hard, one seductive” (Coetzee, Barbarians 8). Even though he does nothing to aide in the torture of the

individuals, he is painfully aware he also does nothing to stop it. This makes him feel guilt and shame for complying with torture, if not executing it, and this emotionally traumatizes him. The Magistrate is troubled by his

connection to Joll, as they are both working for the Empire, and he struggles throughout the novel to personally identify in contrast to the Colonel. Simply witnessing torture causes the Magistrate to feel responsible for Joll’s crimes, and this creates guilt and shame, which provides a motive for his actions later in the novel.

The Magistrate’s transformation as a witness of torture is confined and swollen by his guilt. One of their first dialogues brings the Magistrate to think, “Who am I to assert my distance from him…the Empire does not require that its servants love each other” (6). The Magistrate goes on to oppose Joll in the privacy of his soldiers, saying, “[Joll] is ridiculous!” speaking in reference to the clearly innocent prisoners he has taken (19). However, he still does as Joll commands. As the novel progresses, the Magistrate’s action surrounding Joll changes. He takes in the barbarian girl whom Joll has tortured, seeking to rid his guilt by attempting to heal her. However, this is not enough to disquiet his conscience, as he states: “I undress her, I bathe her…but I might equally well tie her to a chair and beat her, it would be no less intimate” (49). Again he blames himself for aiding Joll as the “innocent bystander.” He still finds himself relating to Joll, thinking “I must assert my distance from Colonel Joll! I will not suffer for his crimes!” (WFB 50). He acts against Joll’s wishes in bringing the barbarian girl to her people, and while imprisoned admits, “I wanted to make reparation” (94). The guilt of witnessing torture is articulated clearly by the Magistrate when he says, “It is the fate of those who witness their suffering to suffer the shame of it” (160). In addition to the Magistrate this occurs to Mandel, Joll’s assistant in torturing operations. He is unable to face the Magistrate when he asks how he can live with the guilt he must feel from being a torturer, and retreats away from him while hitting the Magistrate (146). Many of those who witness torture have the guilt forced upon them– or the shame of seeing torture’s reduction of humanity.

The psyche’s transformation due to a trauma can also be seen in Holocaust memoirs. My grandfather fought in World War II and liberated a Nazi concentration camp with his garrison. Upon seeing the debilitated starving bodies of those who were on the brink of death he and his soldiers vomited at the sight of the very people he came to free. My father would later tell me this, recalling the shame my grandfather felt at seeing those bodies, and the disgust he felt when looking at them. Trauma not only affects the victim, but brings shame and guilt to the witness as well. This is a central theme to Maus, as Artie acts as a witness–a second-‐generation survivor–to the

Holocaust because his parents lived through it. The initial comic depicts a ten or eleven-‐year-‐ old Artie skating with his friends, who skate away without him. He cries to his father that his friends abandoned him. Vladek replies, “Friends? Your Friends? / If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week… / …Then you could see what it is, friends!… (ellipses by Spiegelman, Maus I 6). This is a cynical response from a parent, someone who usually protects children from such vivid imagery, and shows how Vladek raised him with full knowledge of the Holocaust and his experience, even at an early age. Art also witnesses his own trauma directly when his mother commits suicide. Ironically he is expected to console his father instead of grieving with him, as seen in the inserted comic “Prisoner on Hell Planet” (101). Although the reader is left unaware of the trauma this caused Artie, he undoubtedly has deep seeded anger issues with his father over his

upbringing, and struggles to sort through those while simultaneously writing Maus (Maus II 44).

The trauma of the witness is also articulated in Coetzee’s novel Disgrace, through David Lurie. His sexual assault of an adult student, Melanie Isaacs leaves him feeling his own sense of shame and guilt. Although Lurie commits the crime himself, the scene should be treated differently than a traumatic scene with Lurie playing the “evil” villain. The altercation is “undesired to the core,” yet Lurie describes it as “not rape, not quite that” and this notion is strengthened by her helping him undress her (25). This encouragement does not excuse his actions, but simply means there are degrees of rape, and as such Lurie acts as both witness and villain to the trauma. Immediately after Lurie feels remorse for what he has done, calling it “a mistake, a huge mistake” (25). He even mentions a bath may be necessary to cleanse himself of the situation, an action traditionally done by women who are raped, not the perpetrator. Lurie attempts to shed his guilt by marking the Melanie a 70 on her midterm exam even though she was absent. Lurie is a man of conscience, and he tries to reason it was “Aphrodite,” god of love, that spurred him to act (25).

Lurie undoubtedly committed a crime in his assault of Melanie, but his remorse and the severity of the rape make him less a rapist and more a victim of what Freud would call the Id. Lurie is very careful during his preliminary hearing to not apologize for his action, but nevertheless takes his punishment. It would have been easy for David to lie and most likely keep his job, perhaps only suffer a suspension (54). Throughout the novel, he controls his desire even when he feels it, like when he meets the

Melanie’s more attractive sister Desiree: “[David] has an urge to reach

out…at the same instant the memory of [Melanie] comes over him in a hot wave. God save me, he thinks – what am I doing here?” (164). Additionally,

“desire” and “Desiree” can be read equivalently here, and Coetzee did not name Melanie’s sister this by accident. However, he asserts he is guilty of “whatever Ms. Isaacs alleges,” believing there is “no reason she should lie” (49). Lurie makes a calculated distinction here between crime and guilt: he believes he has committed a crime–namely deciding to succumb to his lustful fantasy–but he will not apologize for this original urge. He argues that the fantasy itself is beyond his control, and Lurie states that he often consciously decides not to engage in it. In his assault of Melanie he acquiesces to his darker nature by choice. Having said that, he still adheres to his punishment of disgrace, so much so that he refuses to submit a letter of repentance without sincerity, though a judge at his hearing asks him to (58).

Coetzee’s critique here lies in patriarchal society where those who commit crimes against women are often just told to apologize and they are forgiven. Lurie will not apologize for his own feelings of lust or animalism but nevertheless takes responsibility for his choice of acting on those feelings, and he takes more care throughout the novel to keep them in check, as evidenced by his experience with Desiree.

The trauma of the witness is also portrayed in “Dance with the Devil,” by Coronel. Although the song outlines the corruptive path of the “ghetto-‐bred” youth named William Jacobs who turns to drug dealing, the perspective of the narrator is of a fellow gangster, one whom the main character aims to impress with the gang rape at the end of the song. Ultimately the narrator is similar to Lurie in his shame and regret doing what he did. He sings:

I was there with Billy Jacobs and I raped his mom too

And now the devil follows me wherever I go

In fact, I’m sure he’s standing among one of you at my shows And every street cipher listening to little thugs flow

He could be standing right next to you, and you wouldn’t know

The devil grows inside the hearts of the selfish and wicked White, brown, yellow and black color is not restricted

You have a self-‐destructive destiny when you’re inflicted (Coronel).

Although in no way does his regret excuse his act, the narrator himself now fell victim to the life he is warning others against. Given the intended audience of Corone, it helps that the narrator participates in the crime to add to the ethos of the denunciation of the “live by the gun” mantra. The last lines of the quotation also serve to show that traveling down the path will inevitably cause you to “self-‐destruct,” or “die by the gun.” This is a particularly crucial notion in the ethics of representation because as readers we are all witnesses of the trauma. If we are unaffected by reading the story of a rape, or a torture, clearly the author has not described it well enough. Coronel’s song also holds redemptive power, as the narrator was one of the hardened criminals whom Coronel pleads his audience to avoid. Often witnessing a trauma, as Coronel did can change people for the better, and if even one person is affected enough by “Dance with the Devil” to change their ways, then the song has completed its object.

The Act Itself, And the Impossibility of Telling

J.M. Coetzee writes on the subject of prisons: “[In South Africa] They may not be sketched or photographed, under threat of severe penalty…such laws have a particular symbolic appropriateness, as though it were decreed that the camera lens must shatter at the moment it is trained on certain sites” (“Chamber” 361). This simile can extend to all trauma, and is specifically similar to the common notion that the Holocaust is “unspeakable.” Often it seems that many traumatic events lack a certain “representability,” especially through the medium of language. How can one write about Auschwitz having never been there; describe burning bodies on a blank piece of paper, or a gang rape, or a scene of torture, with only a pen and paper? The clear obstacle in trauma representation is the notion that the act of trauma–meaning the literal murder, rape, or torture–cannot be fully represented simply in words, only a representation can give the reader a notion of the act itself. This is only exemplified by topics surrounding trauma, precisely because the equivocal nature of their portrayal.

Barbarians gives us the Magistrate–referred to Coetzee as “a man of conscience” in his essay “Into the Dark Chamber”–who is confronted directly with torture on three specific instances (364). First, Colonel Joll imprisons him for consorting with the enemy barbarians and left in solitude for three months, repeatedly being denied food and water. Coetzee writes on the depiction of torture in literature: “‘Torture without the

torturer’ is the key phrase…[torture is] beyond the scope of morality. For morality is human, whereas the two figures [tortured] belong to a damned, dehumanized world” (366). His forced solitary confinement acts like this notion of torture in its own way: “I realize how tiny I have allowed them to make my world…I [am] more like a beast or a simple machine…My requests

for clean clothes are ignored…What freedom has been left to me?” (Coetzee, Barbarians 101). The notion of the torture occurring without the torturer is

important because it is what the torturer desires; it is part of the method of torture itself. If the tortured victim fails to see who is torturing him, he will forget his enemy and forget himself. The Magistrate thinks, “they will never bring a man to trial while he is healthy and strong…they will shut me away in the dark till I am a muttering idiot, a ghost of myself,” and this is exactly the aim of torture; not exactly to acquire the truth, just to create something that will say what the torturer needs him to say. The Magistrate’s transformation is similar to methods of torture and degradation used in the Holocaust. The epigraph to Maus I states, “The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human,” which is a quote from Adolf Hitler (Spiegelman 4). Throughout Maus Jews, imprisoned Poles, and other non-‐ Aryan Germans were all treated like animals for the aim of the Nazi cause. Torture makes humans un-‐human, inhumane, and barbaric. Coetzee highlights this dehumanization with the animalistic representation of the Magistrate, and shows that often the tortured loses sight of the torturer.

The Magistrate’s most direct confrontation with torture occurs when he is humiliated in front of the whole town. It then becomes apparent to the Magistrate that Mandel is going to kill him. His walk toward the center of the town is marked by short, halting sentences: “I climb, [Mandel] climbs behind me, guiding me. I count ten rungs. Leaves brush against me. I stop.

He grips my arm tighter” (Coetzee, Barbarians 136). This halting, observational prose starkly contrasts Coetzee’s style earlier in the novel. This stylistic change occurs during the events of torture outside of the Magistrate’s consciousness, and shows that often in order to represent difficult traumas like torture, simple, objective sentences often serve to be more accurate than detailed illustration. By placing these short sentences dispersed throughout, the audience naturally steps inside of the Magistrate’s shoes as he is being tortured and preparing for death. When reading the short sentences readers are compelled to imagine the leaves brushing against themselves rather than viewing the Magistrate’s experience omnisciently. Coetzee ends the torture scene where the Magistrate is hung from his dislocated shoulders with one simple sentence:

“There is laughter” (139). This allows for the reader to feel what it’s like to hang there, if not in pain, at least in experience. While J.M. Coetzee cannot accurately describe what it feels like to be tortured, he can place the reader into a position of empathy, into the shoes of the Magistrate, to imagine what it may be like in his mind, because there is no language which can accurately describe pain to the individual.

This short, iceberg-‐style writing carefully inserts the reader into David Lurie’s position when he is locked in the bathroom during the rape/robbery in his daughter’s house. When describing the actual trauma often Coetzee writes as objectively as possible:

He tries to stand up and is forced down again. For a moment his vision clears and he sees, inches from his face, blue overalls and a

shoe. The toe of the shoe curls upward; there are blades of grass sticking out from the tread (Disgrace 96).

Coetzee inserts the seemingly inconsequential facts, like the blades of grass, to show the effects of trauma on the mind. The brain uses disassociation tactics, or thinking about something completely benign during horrific events to steer itself away from the horror and into action. Another common cerebral response is to enter a “state of hyper-‐

vigilance” (Howard and Crandall, 14). During this time Lurie is on fire, his focus is on blades of grass in a shoe instead of his scalding head. This allows him to quickly assess the location of his enemy while simultaneously allowing the burning to abate while he figures out his next move.

In addition to allowing the reader to insert himself into the text through objective writing, this style complements ethical representation because language often does not do trauma justice. Ernest Hemingway discusses the tabooed topic of abortion in “Hills Like White Elephants,” a short story about an American couple who argue whether or not to abort their child in

a Spanish train station. Hemingway points literally to the inadequacy of the word abortion as representing “abortion” by omitting the word from the

text entirely. The technique serves to heighten the intensity of the text, and leaves the reader guessing at the heart of the narration, while also illustrating the limitations of language. Abortion carries with it many negative connotations relevant to Hemingway’s contemporary reader: defying the religious dogma, the termination of a possible life, as well as breaking the law of the times. Therefore, by omitting the word, the

American man is able to assert abortion is “perfectly simple,” or “perfectly natural” (Hemingway, “White Elephants” 214). The woman clearly feels differently about it, but still does not dare to say abortion, because that would mean absorbing all of its connotations. Instead she simply says she will do it, “because I don’t care about me” (213). This can connect both to the health of the fetus, which the woman feels is a part of her, as well as her own health having an abortion, which can lead to both trauma to the

unborn child as well as the mother. The complexity of language is similarly portrayed in Disgrace, when David Lurie remembers thinking of all the

connotations of the word “rape” as a young man: “[I] wonder what the letter p, usually so gentle, was doing in the middle of a word held in such horror” (160). Through Lurie’s youthful innocence we acquire the important notion that words and language are often disconnected from what they may mean or imply. Particularly in the realm of trauma, words often betray the meaning of those who speak them.

Primo Levi, author of a memoir called Survival in Auschwitz about his experience in the Holocaust, writes, “We became aware that our language lacks words to express this offense, this demolition of man” (26). Often authors insert this notion into their texts to show how difficult it is to truly represent trauma. Inherently, there must be a difference between a representation and the act or thing it is representing, and this dichotomy flirts with the boundary of the ethical. The loss from the act itself to its representation may cause offense, which is why many critics warn against representing difficult traumas like the Holocaust. One way to show the ethical barriers of representing trauma is showing the limitations of language. Spiegelman does this very clearly in Maus II, in which he draws an autobiographical representation of his struggle to represent Auschwitz:

(Maus II 45).

Spiegelman bluntly points out the polarity of describing the indescribable. The third panel shows both Spiegelman and his psychiatrist (an Auschwitz survivor himself) without any speech bubbles after the Beckett quote praising silence. It’s almost as if he is “trying out silence” as a method of Holocaust representation. However, this method clearly is not an effective method of representation; it is the only panel in Maus with no speech bubbles in it, aside from this depiction of Vladek and Artie looking at photos of those who died in the Holocaust:

(Maus II 115).

Here, Spiegelman seems to follow Beckett’s advice, as well as many other Holocaust thinkers who believe that silence is the best method of representation, since the dead cannot speak. This panel acts as a sort commemoration–a “minute of silence”–for those who cannot tell their stories like Vladek can. Spiegelman floods the page with graphics photographs of those who have passed, and they are untied to the normal borders of the novel. They fill in around the page and pile up, so the reader cannot see how many there are. The homage to those who cannot speak is important in ethical representation: while trauma literature often identifies its own limitations in a completely accurate depiction, this does not mean representation is futile. Texts concerning trauma are often self-‐referential

ormetafictionalin nature due to their controversial topics. The self-‐ referentiality of trauma literature is also portrayed in Waiting for the Barbarians. Throughout the novel the Magistrate is unable to discern

exactly what happened to the barbarian girl, other than Colonel Joll’s men tortured her. When asked, the girl responds, “ ‘I am…’–she holds up her forefinger, grips it, twists it. I have no idea what the gesture means” (31). Clearly the girl is gesturing she is broken, but the Magistrate is unable to understand this simple movement, echoing the impossibility of truly representing torture. The Magistrate also attempts to compose a letter, presumably to chastise and oppose Joll’s torture. However, he finds himself unable to write it. He asks himself, “A testament? A memoir? A confession? A history of thirty years on the frontier? All that day I sit at my desk staring at

the empty white paper, waiting for words to come” (66). The Magistrate here acts as a symbol of all authors who attempt to depict torture–or more broadly–trauma. Showing the difficulties depicting trauma is integral to its ethical portrayal. Trauma authors often identify the difficulty–and

sometimes impossibility–of representation of their own topic within their texts. J.M. Coetzee highlights the impossibility of telling in his novel Disgrace

as well.

David Lurie is a literature professor by trade–words are his weapon of choice; accordingly, he wants to use language and speech to publicize the trauma and catch the men who committed the crime. However, Lucy will not let him tell the police of her own trauma, namely rape, but only of his torture (he was burned with alcoholic spirits). She says, “ ‘David, when

people ask, would you mind keeping to your own story, to what happened to you? …I will tell what happened to me’ ” (Coetzee, Disgrace 99). Lucy

repeats herself throughout the novel, even lying to police to avoid accusing the men of rape, and ironically she is not truthful about what happened to her, though she tells David she will be (109). Lucy’s silence parallels Melanie’s silence: neither of their stories are elucidated firsthand. The “unspeakability of rape” is a common trope among canonic literature, and illustrates an important criticism within our culture. Women are not supposed to speak about rape. It is, in Lucy’s words, “a private matter” (102). Lurie even thinks it is “not [his] business,” showing that Coetzee is wrestling whether to represent rape at all (104). If, then, it is not Lurie’s business, and Lucy thinks it a private matter, who has the power of representation? Lurie comments that since Lucy will not speak, the rape has become “not her story to spread but [the rapists’]: they are its owners” (115). Similarly, he believes Melanie views the rape as his secret she must bear (34). The notion of rape becoming a prize for the rapists is something that David opposes, and this opposition is important in the ethics of representation. Just as history is written by the victors, often rape stories are owned by the perpetrators, which Coetzee warns against.

Lurie admits that although he can imagine himself as the men who raped

his daughter, but doubts his ability to imagine himself to be the woman (Coetzee, Disgrace 160). Coetzee does well to bring up this notion throughout Disgrace, and though he illustrates the after effects of rape, he

elides over the act itself. Coetzee highlights a major problem in society by acknowledging that many men cannot imagine what it feels like for women to constantly be in fear of rape, but Lurie knows he must try to imagine

“being the woman” (160). Men must try to be the woman, to empathize with the victim, and the notion that societal norms dictate rape is private complicates this notion. David attempts to reconcile the issues surrounding his own rape and its unspeakability. Coetzee brilliantly outlines the disconnect between men and women on this impassioned issue to show that although rape is a crime, often it goes unreported and unrepresented in both criminal proceedings as well as literature itself.

The topic of rape is incredibly contentious in South Africa, particularly during the publication of Disgrace. President Thabo Mbeka even denounced

the book as racist, and many critics agree that the novel plays to a classic

“black-‐peril” narrative in which the white woman is brutally raped by the “savage” black man (Graham 434). Disgrace also contrasts this by showing

white man’s coercive abuse over minorities through David’s assault of “the dark one,” Melanie (Disgrace 18). It is imperative to understand this text

within the context of the new South Africa and the problems it faced–and still faces. Throughout the novel David Lurie is undoubtedly a protagonist and at his core a good man; he rightfully resigns from his post at the university, he does all he can to protect his daughter, and helps his daughter through her own trauma. However, though we know little of his own political views, Lurie is a liberal who undoubtedly morally opposed Apartheid, yet steered clear from any activism. Petrus, however, is a newly

liberated African, given freedom in a country previously dominated by small upper class whites. Disgrace does not offer a respite or solution to the

opposing forces, but merely shows their contrasting ideology, and Lucy attempts to bridge the two together in her own way: through compassion. David pleads with her to move away when he sees one of the rapists at the

party, but Lucy responds, “This is my life. I am the one who has to live here,” showing that the new South Africa is hers to create (Coetzee, Disgrace 133).

When David catches the younger, mentally troubled rapist named Pollux spying on Lucy, he beats him, feeling “elemental rage” (206). Lucy, however, protects the youth, stopping the violent encounter. Lucy wants above all else to create a harmonious new South Africa, because the country is hers as well. Lucy’s decision to keep the rape a secret also stems from her desire to return to the life she had before the trauma took place, to make peace. However, one critical aspect of the representation of trauma is that the victim is inherently and irreversibly changed due to the act, and they are no longer the person they were before it, no matter how much they may yearn to be.

All the trauma literature I have discussed details the categorical change of

the victim after the trauma. As hard as one may want to return to the way things were, the first step in moving past a trauma is admitting there has been definitive change in who the traumatized person “is.” This is an important notion in trauma representation, especially when many witnesses of trauma fail to see the victims as changed beings and instead treat them as if the trauma had not occurred. David sums up the effect of trauma on the individual clearly in this quotation: “In a while the organism will repair itself, and I, the ghost within it, will be my old self again. But the

truth, he knows, is otherwise. His pleasure in living has been snuffed out” (Coetzee, Disgrace 107). After Lucy’s rape she moves out of her room, the

scene of the crime, refusing to sleep there (111). A less physical change occurs when Lucy does nothing upon hearing Ettinger’s racist remarks about black people, which she would normally “fly into a rage” (109). David Lurie falls prey to pretending Lucy is still her same self during his attempts to persuade Lucy to leave her home, and she replies, “I am not the person

you know” (161). The notion of one dying after a trauma is depicted in Barbarians as well, when the Magistrate speaks to Mandel: “I have already died one death, on that tree” (Coetzee, Barbarians 145). Often instances of

trauma redefine those surrounding the trauma, whether if they realize it or not. In “Hills Like White Elephants” the woman knows that things will be different if she gets an abortion, but the man asserts that their life will be the same. She sarcastically remarks that she knows people that have had abortions and “afterwards they were all so happy” (Hemingway 213). Similarly, the narrator in “Dance With The Devil” remarks that the devil walks around with him, wherever he goes, as a constant reminder of the trauma he endured.

Vladek is also categorically changed from his experience in the camps, and Artie believes this is where Vladek got his miserliness. For example, he tries to return opened cereal boxes, collects copper wire found in the street, and grabs paper towels from restrooms so he doesn’t have to buy them. His wife Mala despairs about this, saying, “All our friends went through the camps. Nobody is like him!” (Spiegelman, Maus II 131). The characterization of Vladek as being miserly his whole life is complicated because the only impression we get of his past is from Vladek’s own perspective. Though he may have always been overly careful or neat, his experience undoubtedly changed him as a person, and intensified his peculiarities. Vladek is a good person overall though, as he selflessly helped Mandelbaum in Auschwitz. Throughout his life Vladek has felt responsible for the people he loves and protected Anja throughout his life, and the notion that he could not save his son Richieu from death has changed him to the neurotic father figure for

Artie. For Vladek, control in his life has always been necessary, and his experience in the camps turned him from a neat individual into a neurotic miserly man.

The Torturer

The most difficult aspect of trauma representation is the question of how to represent the “inducer of trauma”. It is worth noting that although Coetzee only deals with torture in his essay, rapists and perpetrators of genocide can also be thought of as torturers, as all of them use humiliation, pain, and cruelty to dehumanize, kill, or cause its suffering.

Coetzee writes that the problem with representing the torturer to the novelist concerns “how to justify a concern with morally dubious people involved in a contemptible activity…how to treat something that, in truth, because it is offered like the Gorgon’s head to terrorize the populace and paralyze resistance, deserves to be ignored” (Coetzee, “Chamber” 5). This harks back to Adorno’s quotation mentioned earlier in the essay on the characterization of poetry after Auschwitz being “barbaric.” The contrast here, however, is that although Coetzee admits the torturer deserves to be ignored, he does not say he should be, and in his own novels concerning trauma literature does not omit the torturers. Ultimately Coetzee argues that torture lies beneath a moral compass, “for morality is human, whereas [the tortured and the torturer] belong to a damned, dehumanized world,” where the torturer is presumably allowed to do whatever he wants regardless of morals, since he is no longer on the scale of good and evil (Coetzee, “Chamber” 6).

Aside from drawing Germans as cats and Jews as mice, showing the “predator–prey” trope of the Holocaust, Spiegelman’s Maus stands apart from other trauma texts because of its biographical nature. Spiegelman wrote Maus as a memoir of Vladek Spiegelman’s time in Poland and Germany during the war, and he does not focus too much on the representation of the Nazi, instead on the life of a single Jew during the Holocaust. The author makes every Nazi the epitome of evil, both in and out of Auschwitz, which makes sense considering both Vladek’s place and the atrocity committed against so many millions of people. Undoubtedly there were moral Nazis who worked against orders, but since Maus is a memoir, it does not have to tackle the question of representing the torturer, as the torturer is the unambiguous evil Nazi.

Coetzee’s description of torture as being beyond the “scope of morality,” and

thus categorically non-‐human can be read through the lens of the two torturers in Barbarians, Colonel Joll and Warrant Officer Mandel (“Chamber”

6). Canonically eyes are considered “windows to the soul”–Coetzee uses this phrase as well– and humans can read emotions and feeling into people’s eyes, and they are one of the most complex organs in the human body

(Barbarians 145). However, since the first page of the novel we are unable to see Colonel Joll’s eyes because of the “dark disks” he wears, we are unable to view his humanity (1). Joll acts as something inhuman, without feeling, and without a soul. However, when at the end of the novel Joll is driven out of the town and the Magistrate returns as civil servant, they see each other one last time. Joll is in his carriage ready to depart and the Magistrate has an urge to violently punish him. He says:

As though touched by this murderous current he reluctantly turns his face towards me…His face is naked, washed clean…Memories of his mother’s soft breast…as well as of those intimate cruelties fro which I abhor him, shelter in that beehive…The dark lenses are gone (170).

The Magistrate finally sees Joll without his glasses and can see his humanity, even though he is escaping the village. It is almost as if the torturer must keep a façade to mask own humanity so he can torture. The Magistrate is offered a similar view of Mandel. When the Magistrate sees his face he describes his eyes as “clear…as an actor looks from behind a mask” (90). He asks Mandel if he must go through some “purging of [the] soul” after torture, as he cannot imagine being both a human and a torturer. Mandel cannot answer the question, turning violent and shouting vulgarities at the Magistrate (146). Often the torturer is strictly viewed as dehumanized or mechanized, and their struggle to be both human and subhuman is thus an important motif of trauma literature.

Coetzee reminds us in “Into the Dark Chamber” of the isolation and dehumanization of the “tortured” and the disconnect between the torture and the actual man committing the atrocity. The Magistrate escapes his own cell, and watches a scene in which Colonel Joll tortures prisoners he has caught. This seems to contradict Coetzee’s earlier remark about distancing the tortured and the torturer, as Joll is clearly the man responsible for the dehumanization of the Magistrate. Joll, however, insists on the “torture without the torturer” paradigm. He brings out a little girl to whip the prisoners, and certainly a small little girl is an archetype of innocence, and

thus difficult to describe as a “torturer.” From this single instance the crowd

surrounding the scene grapple for the canes, with many taking a turn whipping the prisoners (Barbarians 122). It follows that for the torturer, the

paradigm is advantageous because the victim cannot put a face to the crime, and thus cannot be angry at anything tangible. The Magistrate realizes this because it was happening to him during his isolation, and is why when he sees Joll he becomes incensed. In fact, the Magistrate seems very intent on watching Joll. He says, “Though I am only one in a crowd of thousands, though his eyes are shaded as ever, I stare at him so hard with a face so luminous with query that I know at once he sees me” (121). The Magistrate does not want to reduce torture simply to the act, or his tortured solitude, and Coetzee seems to warn against this characterization, asserting that the men responsible should be tried. However, the Magistrate mentions he cannot do it himself: “Would I have dared to face the crows to demand justice for these ridiculous barbarian prisoners…Easier to shout No! Easier to be beaten and made a martyr” (124). It is difficult to turn the anguish of torture into a call for justice, just as it is difficult for Vladek to relive his Holocaust, and just as Lucy does not accuse the men who raped her, it is easiest to try and forget. However, representation means remembering, and recalling as much as possible, a point Coetzee elucidates through the Magistrate’s confrontation with Joll.

The representation of the rapists in Disgrace is interesting because of the distinctions between David Lurie and the three men who raped Lucy. The relationship between Melanie and David is a complex one, and critics have interpreted David’s forced sexual encounter with Melanie as both a rape as well as simply an “affair [that] blossoms but soon sours” (Graham 440).

David cultivates a relationship with Melanie through their first encounters, and he undoubtedly holds power over her: Melanie is David’s student, he is much older than her, and in a certain sense holds a power from their difference in race within the context of South Africa as Melanie is not white.

David uses his power to seduce Melanie, and on one specific occasion their copulation was “undesired to the core” (Coetzee, Disgrace 25). There are

most definitely degrees of rape, and the violent brutal rape against Lucy is represented much differently than David’s. Two of the three men are never heard from again; it seems they almost don’t deserve to be represented.

The third turns out to be a young mentally challenged boy named Pollux who is related to Lucy’s neighbor Petrus. Pollux ultimately can be sympathized with, because of his mental deficiency, whereas the other men are violent criminals, and are described little, because of their atrocious crimes are left out of representation. Coetzee represents the rape, but not

specifically the rapists, which shows that although rape must be represented, leaving out the perpetrators is important in defining rape ethically. This problem lies beyond the scope of literature, breaking into current event coverage.

This is a current problem in most news stations’ coverage of school shootings: they tend to focus on the perpetrator and not the victims. Elliot Rodger has become a household name, but those he murdered during the 2014 Isla Vista Massacre are less publicized–and unknown outside the sphere of Isla Vista. Dr Park Dietz, a forensic psychiatrist, warns against creating “anti-‐ heroes” out of school shootings, which can lead to further shootings through the high level of coverage about these shootings (“Charlie Brooker’s Newswipe 25/3/09”). However, the media ignored his advice, and since the Isla Vista Massacre, five people died in a Las Vegas shooting, with others occurring in Myrtle Beach and Moncton, Canada. Even upon editing this thesis, another shooting has occurred at Reynolds High School in Troutdale, Oregon on June 10th, 2014 (Springer). In our increasingly global society, it is important to acknowledge the ethics of representation and go about representing difficult topics with care to both depict trauma accurately as well as ensure the trauma does not repeat, which means taking care when “over-‐representing,” glamorizing, or glorifying the torturer, or perpetrator or trauma.

Conclusion

Throughout history authors have struggled with the concept of ethical representation. From Ernest Hemingway to J.M. Coetzee there has been criticism and praise for those who attempt to tackle portraying traumas like

rape, torture, and genocide. J.M. Coetzee received the Booker Prize for Disgrace and his representation of the clash of cultures in South Africa and

two rapes. Answering Cathy Caruth’s question of “how not to betray the past” is difficult, especially when considering representing ethically ambiguous topics, the ultimate difficult topic being the Holocaust. Although it may be difficult, placing the reader into a position to be traumatized is a necessary step in representation. It is the job of literature to sometimes make the reader uncomfortable, and understand what it may be like to live

through a trauma. The reader makes an acknowledgement of this when picking up a novel like Waiting for the Barbarians, and even though it may

not be enjoyable to read about torture, it is necessary to create empathy and compassion for the traumatized. This is the aim of trauma literature, because it is impossible to put someone directly into the shoes of the

traumatized, but to give a representation can enlighten a formerly apathetic individual. It is important to represent honestly, objectively, and accurately. Often apt representation of trauma necessitates objective, cryptic, halting description, which serves to place the reader into the position of the trauma in place of viewing it from afar.

Just as in life everyone will react to a trauma differently, placing the reader into the position of trauma allows the reading to be different based on the reader. The self-‐referentiality of trauma literature is also crucial in accurate objective representation. All of the texts I’ve discussed question their own ethics, precisely because rape, genocide, and torture are such difficult topics to grapple The self-‐referential nature of the texts allow for a more accurate representation because depicting these topics is not easy. Finally, the representation of the torturer is difficult because the act of torture in subhuman, and utterly unnatural. Because of this the torturer is represented as un-‐human. Though true ethical representation is difficult, there should be no trauma that can go textually unrepresented. Though the Nazi or the rapist certainly deserves to be forgotten amidst history’s books, this does not mean he should be. As societal critics and historicists it is the obligation of the author to accurately represent things that may not deserve to be represented. However, this does not allow them to escape judgment and remembrance. Nazism, rape, torture–all were created and perpetrated by humans in the most literal sense, and because of this they cannot be forgotten. Closure from trauma is from compassion, acceptance, and empathy.

A Brief Coda

During these past ten weeks I have spent countless hours reading, writing, editing and re-‐ editing my thesis on how to represent the “un-‐ representable.” On May 23, 2014, a devastating mass shooting took place in my college community of Isla Vista, killing seven people and injuring thirteen more. I was not in Isla Vista when this occurred–I was on the road to Las Vegas, a trip meant to celebrate our near-‐completion of college. After phoning everyone I knew to ascertain whether they were safe, I realized that my friends and I were all physically unharmed from the killing. Despite this I still felt deeply saddened by what happened, and asked myself a question so many probably did, why? Every time a car drives slowly by me, my heart jumps into my throat.

Over the next few weeks I watched, unsure of how to continue writing, as

everyone else picked up their pens and keyboards. People who never post to Facebook were posting “solidarity” statuses, Twitter was ablaze with #Yesallwomen and later #Notonemore, and major news networks filled their airtime with their trauma porn. The immediate politicization of the incident was a little shocking, and of course the perpetrator’s manifesto and his Youtube videos added to the fiasco. Richard Martinez, father of one of the victims, vehemently spoke for gun control in the wake of the murders, and a Dr. Robi Ludwig suggested it could have been his “homosexual tendencies” that provoked the man to murder (“Fox News”).

More than ever I am convinced the ethics of representation does not simply take place in the classroom, or the library. It takes place in our lives everyday. I did not know how to write after the massacre, and spent much of the next week playing basketball to slow my own brain down, un-‐think, to forget. The reality of the trauma hits everyone in different ways, for me trauma has always been dealt with through sports, my own escape from thought–where the debilitating “Why” question fades away on the court. However, representation of difficult topics must occur, and there exists a tactful method for this. Just as history books do not tell the whole story, neither did CNN nor Fox News. They did not comment on the protesters outside their vans, who pleaded with them to go, to please leave us alone. They ignored Dr. Dietz’s warning about creating an anti-‐hero, and four more shootings have taken place around the United States and Canada in the span of three weeks. All of my work on theory and the literary texts which I looked to could not prepare me for driving back to Isla Vista’s haunted streets on Tuesday, the “Day of Mourning” decreed by the University of California. All this defense of representation and here I am, unable to write about the massacre myself! Life often acts thus, it is the most brutal of ironies. Although it may be simpler for the outsider to depict my own trauma, it is up to one of us (or more), to sacrifice our own method of coping, to write, sing, act, or paint our own truth of the Isla Vista Massacre– many people have already been doing this. All around Isla Vista I see survivors. Soon, when a car drives slowly by, I know my heart will leap from my chest no longer.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. “Cultural Criticism and Society.” Prisms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981. Print.

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins UP, 1996. Print.

Coetzee, J.M. Disgrace. New York: Penguin, 2000. Print.

-‐-‐-‐. Waiting for the Barbarians. New York: Penguin, 1982. Print.

Coetzee, J. M., and David Attwell. “Into The Dark Chamber.”

Doubling the Point: Essays and Interviews. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1992. 361-‐ 68. Print.

“Fox News ‘expert’ suggests ‘homosexual impulses played a role in Calif. massacre.” lgbtqnation.com. Youtube.com, 25 May 2014. Web. Accessed 12 June 2014.

Fry, Paul. Theory of Literature. New York: Yale University Press, 2012. Print. Graham, Lucy Valerie. “Reading the Unspeakable: Rape in J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace.” Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2003): 433-‐444. Jstor. PDF. Accessed 26 May 2014.

Hemingway, Ernest. “Hills Like White Elephants.” The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. New York: Scribner’s, 1987. 211-‐14. Print.

Howard, Sethanne and Mark W. Crandall, MD. “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: What Happens in the Brain?” Washington Academy of Sciences, Fall 2007. Web. Accessed 27 May 2014.

Immortal Technique. “Dance With The Devil.” Revolutionary Vol. 1. Comp. Felipe Coronel. Viper Records, 2001. MP3.

Katoi. “Charlie Brooker’s Newswipe 25/03/09.” Online Video Clip. Youtube. Youtube, 25 March 2009. Web. Accessed 1 June 2014.

Levi, Primo. Survival in Auschwitz. New York: Touchstone, 1996. Print.

Population Reference Bureau. “Children in Single-‐Parent Families By Race.” National Kids Count. Feb 2014, Tab. 1a. Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014. Web.

Accessed: 20 March 2014.

“Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.” American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association, 2014. Web. Accessed 10 June 2014.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History. New York:

Pantheon, 1986. Print.

-‐-‐-‐. Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began. New York: Pantheon, 1991. Print.

Springer, Dan. “Gunman in fatal Oregon high school shooting likely killed self, police say.” Fox News. Fox News and Associated Press, 10 June 2014. Web. Accessed 10 June 2014.